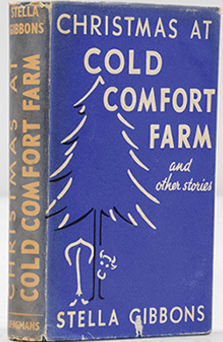

The short story can be found in

the collection by the same name.

Last night was the year's longest night, which means it is probably fitting to bring in

Cold Comfort Farm. If you have no idea what I am talking about, you should go remedy that; Stella Gibbons is well worth your time: It is a glorious parody of the dour rural melodarama of the D. H. Lawrence/Mary Webb school, sometimes disparagingly called "loam and lovechild" (especially, perhaps, Mary Webb's

The Golden Arrow, which Gibbons was allegedly writing plot summaries of when she had enough). If you are somehow allergic to books (or have already read it), there is a rather good adaptation with Joanna Lumley, Eileen Atkins, Kate Beckinsale, Ian McKellen, Stephen Fry and Rufus Sewell (though it leaves out one of the things I find most interesting about the book: the incidental science fiction).

Today's story is the prequel to this glorious piece of fiction. I would recommend reading the original novel, and some of the humour of the Christmas story may be lost if you do not. To offset that, allow me to tell you a little about it.

Cold Comfort Farm tells the story of Flora Poste, a sensible young woman from London who has lost both her parents and as a result decides to go live with her relations in Sussex, the Starkadders at Cold Comfort Farm. Following tradition, she should discover the glory of traditional values while there; but instead, Flora sets out to clean up the farm and its people, dragging the family into the 20th century, armed with her book on

Higher Common Sense. As the book states in its opening lines,

The education bestowed on Flora Poste by her parents had been expensive, athletic and prolonged.

and she uses it to great effect (though does not follow that Flora herself is not gently mocked). The meeting between her and the dark, dirty, dour world of the Starkadders is glorious. In part because of the continued references to a curse on the farm, and the cryptic references to some terrible wrong committed against Flora's father (always present, as the family keeps referring to her as "Robert Poste's child"), and lovely, silly lines like

One of the disadvantages of almost universal education was the fact that all kinds of persons acquired a familiarity with one's favourite writers. It gave one a curious feeling; it was like seeing a drunken stranger wrapped in one's dressing gown.

And, as I indicated earlier, almost incidental science fiction; for the novel was written in 1932, over 70 years before Skype was invented, and yet you get references like this:

Claud twisted the television dial and amused himself by studying Flora's fair, pensive face. Her eyes were lowered and her mouth compressed over the serious business of arranging Elfine's future. He fancied she was tracing a pattern with the tip of her shoe. She could not look at him, because public telephones were not fitted with television dials.

Right in between the cows and the 1930s social and cultural references. I am sure that by now, if you have not read the book you have already ordered it (or sent someone out to fetch it for you), so I will immediately progress to the text of the day.

"Christmas at Cold Comfort" farm is set before the arrival of Flora Poste, and we therefore get to see the Starkadders undiluted, as it were. The short story opens,

It was Christmas Eve. Dusk, a filthy mantle, lay over Sussex when the Reverend Silas Hearsay, Vicar of Howling, set out to pay his yearly visit to Cold Comfort Farm.

The description of dusk says it all, really. The farm and the people in it are described in such exaggerated terms of dirt and despair throughout. The perspective of the Vicar is quickly faded out, but it is a useful way into the madness.

The Starkadders, of Cold Comfort Farm, had never got the hang of Christmas, somehow, and on Boxing Day there was always a run on the Howling Pharmacy for lint, bandages and boracic powder. So the Vicar was going up there, as he did every year, to show them the ropes a bit.

The description of the kitchen as he enters is characteristic.

the desolate kitchen, at the dead blue ashes in the grate, the thick dust on hanch and beam, the feathers blowing about like fun everywhere. Yet even here there were signs of Christmas, for a withered branch of holly stood in a shapeless vessel on the table.

This is the only time the word "fun" appears in the story. The other elements of Christmas cheer are treated much like the poor branch of holly. The old (very old) farmhand Adam is dressed in three red shawls in an attempt to look like Father Christmas, and the

traditional Christmas pudding is made with fairly particular items of (unconventionally bad) luck:

'Now, missus, have ee got the Year's Luck? Can't make puddens wi'out the Year's Luck,' said Adam, shuffling forward.

'It's somewhere here. I forget ---'

She turned her shabby handbag upside down, and there fell out on the table the following objects:

A small coffin-nail.

A menthol cone.

Three bad sixpences.

A doll's cracked looking-glass.

A small roll of sticking-plaster.

Adam collected these objects and ranged them by the pudding basin.

'Ay, them's all there,' he muttered. ' Him as gets the sticking-plaster'll break a limb; the menthol cone means you'll be blind wi'headache, th ebad coins means as you'll lose all yer money, and him as gets the coffin-nail will die afore the New Year. The mirror's seven years' bad luck for someone. Aie! In ye go, curse ye!' and he tossed the objects into the pudding, where they were not long distinguishable from the main mass.

Before the pudding can be eaten, however, Christmas Eve becomes night, and Adam goes through the house in his role as Father Christmas:

At midnight, when the farmhouse was in darkness, save for the faint flame of a nightlight burning steadily beside the bed of Harkaway, who was afraid of bears, a dim shape might have been seen moving stealthily along the corridor from bedroom to bedroom. It wore three red shawls pinned over its torn nightshirt and carried over its shoulder a nose-bag (the property of Viper the gelding), distended with parcels. It was Adam, bent on putting into the stockings of the Starkadders the presents which he had made or bought with his savings. The presents were chiefly swedes, beetroots, mangel-wurzels and turnips, decorated with ribbons and strips of paper from tea packets.

It is not an unqualified success. He finds a suspicious Mrs Beetle (the one rather sensible person in the farm) guarding the room where the young Meriam (a hired girl who in the novel is more or less constantly pregnant with the children of the oversexed son of the farm, Seth) is sleeping; Seth is busy with a "friend" and not happy about being interrupted; and when he gets to the room of the preacher Amos, who regularly preaches about hellfire and damnation to his congregation of the Quivering Brethren (father of Seth and husband to Judith Starkadder),

Amos was praying, and did not even get up off his knees or open his eyes as he discharged at Adam the goat-pistol which he kept ever by his bed.

Nor do things improve with the rest, as the presents fall out of the enormous holes in the stockings of the Starkadders, leaving them to be stepped on in the following morning.

So what with one thing and another everybody was in an even worse temper than usual when the family assembled around the long table in the kitchen for Christmas dinner.

Where, moreover, the gothic horror of the Starkadder Christmas decorations is rather impressive.

Adam gave a last touch to the pile of presents, wrapped in hay and tied with bast, which he had put around the foot of the withered thorn-branch that was the traditional Starkadder Christmas-tree, hastily rearranged one of the tufts of sheep's-wool that decorated its branches, straightened the raven's skeleton that adorned its highest branch in place of a fairy-doll or star, and shuffled into place just as Mrs Doom reached the foot of the stairs, leaning on her daughter Judith's arm.

Ada Doom (Gibbons' character naming rivals Dickens'), the family matriarch, is also in top form:

'Amos, carve the bird. Ay, would it were a vulture, 'twere more fitting! ... Be gay, spawn! Laugh, stuff yourselves, gorge and forget, you rat-heaps! Rot you all!'

And Judith's overture to her husband falls gloriously flat:

'Amos, will you pull a cracker wi' me? We were lovers ... once.'

'Hush, woman.' He shrank back from the proffered treat. 'Tempt me not wi' motters and paper caps. Hell is paved wi' such.' Judith smiled bitterly and fell silent.

The atmosphere improves when the pudding arrives, however:

A stir of excitement now went through the company, for everybody looked forward to seeing everybody else drawing ill-luck from the symbols concealed in the pudding.

And they have great fun tracing who will lose their money and who will break their bones, until all that remains is the coffin-nail, the harbinger of death. It turns out Mrs Beetle has taken it out of the pudding because she got tired of the expectant glances they gave the boy who got it the preceding year. After such a shock, Mrs Doom can only be appeased by the arrival of a present, the main value of which is that it gathers all the magazines she uses to beat her family with into one handy, heavy volume that can be

thrown. Chaos ensues.