Christmas stories: The Festival

05.12.14

00:05

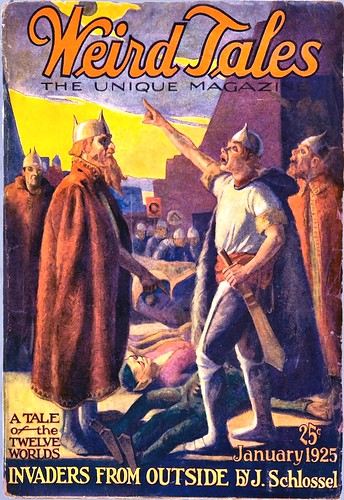

"The Festival" was first published in the January

1925 issue of the pulp magazine Weird Tales.

I suspect your first thought as Christmas approaches is not Lovecraftian horror, though it is not as incongruous as you might think.

There is a long tradition tying the winter solstice to dark happenings (think the Asgaardsrei, for example), and people like M. R. James have had a lot of fun scaring their friends silly over the holidays. I am generally not of this persuasion (being the scaree more often than the scarer), but it is hard to bypass H. P. Lovecraft's "The Festival" in this context of Christmas stories.

It was originally published in

Weird Tales, but you can read it

here (not for the faint-hearted -- in fact, if you dislike horror, you may reconsider reading this particular entry; go

watch this kitten instead. There is no shame in this).

I have not, however, chosen a scary tale just for the sake of tradition. "The Festival" IS a Christmas story, after a fashion. And it is set in New England. Now, that sounds innocent enough, doesn't it?

It was the Yuletide, that men call Christmas though they know in their hearts it is older than Bethlehem and Babylon, older than Memphis and mankind. It was the Yuletide, and I had come at last to the ancient sea town where my people had dwelt and kept festival in the elder time when festival was forbidden; where also they had commanded their sons to keep festival once every century, that the memory of primal secrets might not be forgotten.

Of course, where winter solstice festivals in general are about the death of the world around us, the darkness and the cold, changed into the hope that that is changing, that the sun will come back and things will get green again (the main message of all those evergreen decorations), in Lovecraft the death and cold and horror is just how things are. And more specifically, it is set in Lovecraft's fictional part of New England, in the town of Kingsport, south of (the equally fictional) Arkham, which features elsewhere in the Cthulhu stories. And in case there was any doubt, this is part of that cycle. It is in fact one of the first stories to quote extensively from the

Necronomicon, and it also provides some of the background of that (fictional) book:

the books were hoary and mouldy, and that they included old Morryster’s wild Marvells of Science, the terrible Saducismus Triumphatus of Joseph Glanvill, published in 1681, the shocking Daemonolatreia of Remigius, printed in 1595 at Lyons, and worst of all, the unmentionable Necronomicon of the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred, in Olaus Wormius’ forbidden Latin translation; a book which I had never seen, but of which I had heard monstrous things whispered.

...

So I tried to read, and soon became tremblingly absorbed by something I found in that accursed Necronomicon; a thought and a legend too hideous for sanity or consciousness.

I'll get back to that. First, however, the main character has arrived in Kingsport, summoned by his forefathers to participate in a rite. All is still and quiet, and he knocks on the designated door. He is seized by an unexplained fear, though it quiets when the mute man who answers it looks so thoroughly normal. After a while, however,

This fear grew stronger from what had before lessened it, for the more I looked at the old man’s bland face the more its very blandness terrified me. The eyes never moved, and the skin was too like wax. Finally I was sure it was not a face at all, but a fiendishly cunning mask. But the flabby hands, curiously gloved, wrote genially on the tablet and told me I must wait a while before I could be led to the place of festival.

This idea of the human appearance as a mask that hides the horror of the other is classic Lovecraft. The horror is inspired by the shapelessness of it all, that it is a thing which escapes language and classification. As you will see (unless you want to stop now and go look at the kitten; I won't hold it against you).

They head to the place of the festival. And not alone.

the Dog Star leered at the throng of cowled, cloaked figures that poured silently from every doorway and formed monstrous processions up this street and that, ... threading precipitous lanes where decaying houses overlapped and crumbled together, gliding across open courts and churchyards where the bobbing lanthorns made eldritch drunken constellations.

Amid these hushed throngs I followed my voiceless guides; jostled by elbows that seemed preternaturally soft, and pressed by chests and stomachs that seemed abnormally pulpy; but seeing never a face and hearing never a word.

Eldritch, incidentally, is a word I first found in Lovecraft, and one which has remained Lovecraftian to me ever since. The eerie procession goes far down into the bowels of the earth, and the sense of decay and old evil increases. It does not reach a happy place.

Fainting and gasping, I looked at that unhallowed Erebus of titan toadstools, leprous fire, and slimy water, and saw the cloaked throngs forming a semicircle around the blazing pillar. It was the Yule-rite, older than man and fated to survive him; the primal rite of the solstice and of spring's promise beyond the snows; the rite of fire and evergreen, light and music. And in the Stygian grotto I saw them do the rite, and adore the sick pillar of flame, and throw into the water handfuls gouged out of the viscous vegetation which glittered green in the chlorotic glare. ... But what frightened me most was that flaming column; spouting volcanically from depths profound and inconceivable, casting no shadows as healthy flame should, and coating the nitrous stone above with a nasty, venomous verdigris. For in all that seething combustion no warmth lay, but only the clamminess of death and corruption.

You will have noticed by now that Lovecraft does not believe in naked language. He throws everything at you, only to in the end abandon it as insufficient:

Then the old man made a signal to the half-seen flute-player in the darkness, which player thereupon changed its feeble drone to a scarce louder drone in another key; precipitating as it did so a horror unthinkable and unexpected. At this horror I sank nearly to the lichened earth, transfixed with a dread not of this nor any world, but only of the mad spaces between the stars.

Out of the unimaginable blackness beyond the gangrenous glare of that cold flame, out of the Tartarean leagues through which that oily river rolled uncanny, unheard, and unsuspected, there flopped rhythmically a horde of tame, trained, hybrid winged things that no sound eye could ever wholly grasp, or sound brain ever wholly remember. They were not altogether crows, nor moles, nor buzzards, nor ants, nor vampire bats, nor decomposed human beings; but something I cannot and must not recall.

The horror of the thing can only be approached in the negative: It is not this, not that; it cannot be described in language nor grasped by the mind. And we are not yet arrived at the heart of the Yule festival.

As I hung back, the old man produced his stylus and tablet and wrote that he was the true deputy of my fathers who had founded the Yule worship in this ancient place; that it had been decreed I should come back, and that the most secret mysteries were yet to be performed. He wrote this in a very ancient hand, and when I still hesitated he pulled from his loose robe a seal ring and a watch, both with my family arms, to prove that he was what he said. But it was a hideous proof, because I knew from old papers that that watch had been buried with my great-great-great-great-grandfather in 1698.

...

When one of the things began to waddle and edge away, he turned quickly to stop it; so that the suddenness of his motion dislodged the waxen mask from what should have been his head. And then, because that nightmare’s position barred me from the stone staircase down which we had come, I flung myself into the oily underground river that bubbled somewhere to the caves of the sea; flung myself into that putrescent juice of earth’s inner horrors before the madness of my screams could bring down upon me all the charnel legions these pest-gulfs might conceal.

And so, the true ritual is left undescribed, for us to imagine based on all the dreadful hints and indications that suggest even its preliminaries are too much for the human mind to handle. The combination of the bodily not-quite-right with a touch of gory, and the explicitly unspoken, unutterable, avoided heart of it works like a charm on my overactive imagination. I try not to read Lovecraft too often.

The story is not quite over, however. The narrator, having flung himself into the river, wakes up in a hospital in a Kingsport that is altogether more modern than the one he visited at Christmas. He is told that he never made it to the town. But when they tell him the hospital he is in is next to the town's old cemetery, he gets delirious and is sent on to Arkham, where he gains access to the translation of the

Necronomicon, finding again the section he read in Kingsport (which his doctors claim never happened).

There was no one—in waking hours—who could remind me of it; but my dreams are filled with terror, because of phrases I dare not quote. I dare quote only one paragraph, put into such English as I can make from the awkward Low Latin.

“The nethermost caverns,” wrote the mad Arab, “are not for the fathoming of eyes that see; for their marvels are strange and terrific. Cursed the ground where dead thoughts live new and oddly bodied, and evil the mind that is held by no head. Wisely did Ibn Schacabao say, that happy is the tomb where no wizard hath lain, and happy the town at night whose wizards are all ashes. For it is of old rumour that the soul of the devil-bought hastes not from his charnel clay, but fats and instructs the very worm that gnaws; till out of corruption horrid life springs, and the dull scavengers of earth wax crafty to vex it and swell monstrous to plague it. Great holes secretly are digged where earth’s pores ought to suffice, and things have learnt to walk that ought to crawl.”

Keep this in mind if things get iffy at Christmas: As long as your relatives are not creepy worshippers of Elder Gods, bringing you into deep dank caves to perform rites with insanity-inducing creatures, you are basically doing all right. Unless, of course, they just haven't told you yet.

Comments