A week or so ago, Tor and I were buying a gift for a six-year-old girl. Morally opposed to buying anything pink or glittery, and having been told that age six is too young for a chemistry set, we decided on a book of experiments. Every six-year-old should have one. I know this because I did not have one growing up, and as a result I was 16 before I was introduced to the magic that is corn starch (or, since we are in Norway, potato starch) in water. And from what I have been told, Karoline has yet to encounter it. I will remedy this at the first opportunity and see if I can't furnish a video of the event.

But this is not the story of the lack of science in my childhood (it was a perfectly happy one, filled with musketeers and hobbits, so I am not really complaining).

This is the story of how we discovered the magical properties of water.

I know, I know. It keeps the planet alive and makes us something other than heaps of dust and so on. But that is not the magic I am talking about. Nor am I planning to make some sort of insane claim about water having memory or somehow being able to furnish free energy forever. This is about the magic of cutting glass under water with your kitchen scissors.

It sounds like pure fiction. And I should know. Then again, much science does.

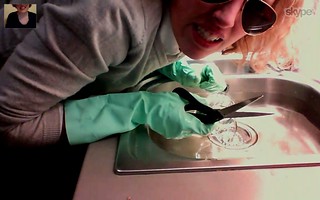

So, when Tor went off and left me to myself this weekend, my inner experimentalist came out to play. My inner experimentalist is not the most adventurous scientist around and I had little belief in my ability to do this kind of experiment without accidentally blinding myself or cutting vital veins with a spray of glass. I solved this through the magic of Skype, by calling up my sister and telling her of my plans.

Much more adventurous than me, she went off and found some protective eye-wear, a glass, some scissors and a friendly assistant armed with the number for emergency services.

Much more adventurous than me, she went off and found some protective eye-wear, a glass, some scissors and a friendly assistant armed with the number for emergency services.

These should not be scissors you love very much, because they may never be the same again.

You may also want to keep in mind that the glass will be utterly destroyed by the experiment, and you should therefore not use a precious family heirloom or anything from the 17th century. Try cutting the glass above water. It does not work.

Try cutting the glass above water. It does not work.Then, put on your Dr Horrible gloves (for your own comfort &c.), fill the sink with water and get to it.

Make sure you hold the glass under water while you cut. This is central to the execution of the experiment, and if you don't you might as well be reading a good book.

Make sure you hold the glass under water while you cut. This is central to the execution of the experiment, and if you don't you might as well be reading a good book. A large piece will break off.

A large piece will break off.

This is because the glass is not only round, but also tense and brittle and unwilling to go with the flow. Claims on the internet that this is like cutting cardboard are therefore wild exaggerations and should be disregarded. You may now want to try cutting the glass above the water again (just to see whether getting it wet and loosening it up did the trick. It still does not work.

You may now want to try cutting the glass above the water again (just to see whether getting it wet and loosening it up did the trick. It still does not work.  Note that glass is sharp like a very sharp thing, and after cutting chunks out of it it may begin to look a little scary.

Note that glass is sharp like a very sharp thing, and after cutting chunks out of it it may begin to look a little scary. Take care not to cut yourself. Rubber gloves do not really offer that much protection.

Take care not to cut yourself. Rubber gloves do not really offer that much protection.  Cutting your finger really hurts.

Cutting your finger really hurts.  I'm not joking. It gets really, really sharp. Deadly in the wrong hands. Especially if you get a little carried away with the cutting.

I'm not joking. It gets really, really sharp. Deadly in the wrong hands. Especially if you get a little carried away with the cutting.  Having ascertained the efficacy of tepid water, Calcuttagutta's intrepid experimenting duo wondered whether reducing the temperature would affect the cuttability (now a word) of glass.

Having ascertained the efficacy of tepid water, Calcuttagutta's intrepid experimenting duo wondered whether reducing the temperature would affect the cuttability (now a word) of glass.  The glass itself having attacked Karoline once, we left it to one side and tried cutting one of the larger pieces.

The glass itself having attacked Karoline once, we left it to one side and tried cutting one of the larger pieces.The result was even more impressive, but because we were fast running out of glass we could not ascertain whether this was due to the temperature or simply because cutting a piece in two is easier than cutting through the tension of curved glass.

At any rate, there can be no doubt about the success of our experiment. We have successfully proven that physics is magical and water can help you cut glass.

Now if someone would just tell us WHY.

Much more adventurous than me, she went off and found some protective eye-wear, a glass, some scissors and a friendly assistant armed with the number for emergency services.

Much more adventurous than me, she went off and found some protective eye-wear, a glass, some scissors and a friendly assistant armed with the number for emergency services.  Make sure you hold the glass under water while you cut. This is central to the execution of the experiment, and if you don't you might as well be reading a good book.

Make sure you hold the glass under water while you cut. This is central to the execution of the experiment, and if you don't you might as well be reading a good book. A large piece will break off.

A large piece will break off. You may now want to try cutting the glass above the water again (just to see whether getting it wet and loosening it up did the trick. It still does not work.

You may now want to try cutting the glass above the water again (just to see whether getting it wet and loosening it up did the trick. It still does not work.  Note that glass is sharp like a very sharp thing, and after cutting chunks out of it it may begin to look a little scary.

Note that glass is sharp like a very sharp thing, and after cutting chunks out of it it may begin to look a little scary. I'm not joking. It gets really, really sharp. Deadly in the wrong hands. Especially if you get a little carried away with the cutting.

I'm not joking. It gets really, really sharp. Deadly in the wrong hands. Especially if you get a little carried away with the cutting.  Having ascertained the efficacy of tepid water, Calcuttagutta's intrepid experimenting duo wondered whether reducing the temperature would affect the cuttability (now a word) of glass.

Having ascertained the efficacy of tepid water, Calcuttagutta's intrepid experimenting duo wondered whether reducing the temperature would affect the cuttability (now a word) of glass.  The glass itself having attacked Karoline once, we left it to one side and tried cutting one of the larger pieces.

The glass itself having attacked Karoline once, we left it to one side and tried cutting one of the larger pieces.

Comments